Susan is a 2021 fellow with Grassroot Soccer and she is currently based in Kenya. She is passionate about social impact projects and has worked on Adolescent SRHR projects with LVCT Health Kenya and Ark Africa. She’s also worked on projects related to healthcare in urban slums and waste management at the Nairobi Design Institute. Most recently, she worked with Dalberg Media and Merck Group on a project to help eradicate bilharzia in Kenya. With a Master’s degree in Human Computer Interaction Design from City University of London and an MBA in Business Information Systems from Turku School of Economics in Finland, Susan hopes to use her knowledge and skills to help Grassroot Soccer build a strong foundation in youth-powered design.

Susun was interviewed on April 8, 2021

Let’s start with an introduction. Can you tell me a little bit about yourself and your work?

My name is Susan Towett. I am a Kenyan citizen, born and raised in the Rift Valley region. I identify myself with the buffalo clan, within the highland Nilotes community here in Kenya. My sustained interest in technology led me to study Business Information Technology, and then a few years later I pursued a Master’s degree in Human Computer Interaction Design. I’m interested in using technology for social good and I am trying to get involved in projects that focus on such. In January 2021, I was involved in two amazing projects. One was about using storytelling techniques to spread awareness about ways to eliminate bilharzia, and the other was about introducing an SRH website that targeted 10-24-year-olds in Kenya. This particular website covered issues such as gender-based violence, family planning, HIV, STI testing, mental health, and much more. I did this project with LVCT Health Kenya, and they launched the website in mid-February this year. Soon after that I joined the HCDExchange Fellowship Programme and I’m very fortunate to be one of three Design Fellows in the first cohort of the programme.

What attracted you about the HCDExchange Fellowship?

I was really interested in advancing my knowledge and practical experience within the adolescent sexual and reproductive health field based on my experience with three projects that I have previously done. Besides the LVCT health care project that I have already told you about, I also did two other projects – one was with the Nairobi Design Institute in early 2019 which birthed my interest in ASRH. When I came across the Fellowship I thought it would help me build my HCD skills, and help me learn more about ASRH programming design. I felt like it was a perfect fit for me. So I applied for the Design Fellowship Programme, and I was lucky to be selected by Grassroot Soccer as the host organisation.

Can you tell me about Grassroot Soccer and the project that you’re currently working on?

Grassroot Soccer (GRS), is an organisation that uses soccer as a fun way to teach adolescents and young adults about SRH, gender-based violence, HIV and much much more. For instance, if we were to focus on HIV prevention tactics, I can say that GRS delivers vital HIV or AIDS knowledge to young people through a SKILLZ curriculum which addresses HIV or AIDS prevention, by teaching adolescents and young adults about risky behaviors, along with basic facts about HIV and AIDS. GRS has trained local mentors, who are known as Coaches, and they incorporate soccer into lessons about health and wellness. This gets young people to really engage and learn about SRH topics in a simple and open manner. GRS also organises a day of soccer tournaments combined with access to free HIV testing and counseling services, as well as access to information and services regarding things such as voluntary medical male circumcision, which is a very important strategy for HIV prevention. They further ensure that they offer a safe and inclusive environment for HIV positive youth to openly discuss any concerns and support each other in adhering to HIV treatment. This is just one good example of how GRS uses soccer to teach adolescents and young adults about SRH issues.

As a Design Fellow, one of the projects I have been involved with is Youth-Powered Ecosystem to Advance Urban Adolescent Health and Well-Being (YPE4AH). YPE4AH is a USAID-funded, 5-year project in Nigeria, aiming to improve the health and well-being of urban, underprivileged, out-of-school, unmarried adolescents, aged 15 to 19, by increasing uptake and continued use of voluntary family planning. YPE4AH is being implemented by a consortium of five partner organisations: DAI, Yellow Brick Road, Youth Empowerment Development Initiative, Women Friendly Initiative, and Grassroot Soccer. The project areas include Lagos and Kano State which are the two largest urban areas in Nigeria with very diverse cultural and socio-economic context. YPE4AH has a youth advisory committee, and aims to engage government representatives, private sector and civil society stakeholders, and other health personnel who are critical to advocate for improved adolescent life skills, leadership skills and livelihoods.

YPE4AH project design centres around Youth Hubs, which are basically safe spaces for youth to seek and access family planning and SRH information and referrals. The Youth Hubs will also establish ‘spokes,’ which are youth friendly services not offered by the hubs themselves, for example – services around gender-based violence. The YPE4AH programme also SKILLZ Curricula which combines sports and fun based activities to start healthy behavior and shift attitudes for more equitable gender norms. Additionally, YPE4AH will build youth leadership skills through a programme called Champions for Change. YPE4AH also focuses on livelihoods, which is really about increasing youth workforce readiness, job opportunities, entrepreneurship, and this will help the adolescents address issues related to access to SRH needs and challenges.

YPE4AH aims to integrate HCD throughout project design, implementation, and evaluation, beginning with formative research conducted by consortium consultants. The formative research key findings covered three main areas – 1) the behaviours and current understanding of family planning and SRH needs for 15 to 19-year-olds, 2) the political and economic landscape of Lagos and Kano State as it pertains to adolescent health and well-being, and 3) the health system structure and processes for adolescent family planning and SRH programming. The findings were incorporated into a programme design workshop (PDW) with all consortium partners, held in late March 2021. During the PDW, participants ideated and prototyped initial concepts around how the Youth Hubs will look, the activities that will take place in the Hubs, services that will be offered by Hubs and Spokes, and the kinds of personnel that can either work at or visit the Hubs (healthcare providers, technical personnel, parents, media representatives, celebrities etc). Synthesis of the PDW outputs led into an additional Curriculum Development Workshop (CDW), held in May.

How does Human Centered Design fit into the work that you are doing at Grassroot Soccer?

YPE4AH consortium partners are all committed to meaningful youth engagement, and in preparation for the PDW and CDW, the group had internal meetings to brainstorm ways to encourage youth engagement and active participation. One idea that proved successful was to develop WhatsApp videos to introduce the workshop and objectives in a very youth friendly manner to the youth participants. The consortium had also selected pre-reading materials for PDW participants, and after discussion, adapted the language of the materials to make them less technical and more suitable for 15 to 19-year olds.

Another project I’m working on is to create a Youth Powered Design toolkit for GRS. GRS wants the toolkit to provide clear guidance on youth powered design processes for use globally. One example of youth powered design through GRS research is what they call youth participatory action research. In GRS words, it is “an approach to social change, centered on the principle of social justice and equity that engages youth to identify and solve problems relevant to their own lives.” So through this youth participatory action research GRS trains participants as youth researchers, and they conduct the research, evaluate programming including data collection, analysis and synthesis with peers and adult researchers. This approach also supports youth to present and utilise the research. They help disseminate findings by presenting to key stakeholders in their schools and communities, as well as to other stakeholders in regional and international meetings and conferences. The Youth Powered Design toolkit that I’m working on will provide the templates for this, and the tools for the formative research, design and implementation phases of the design process.

Based on what you said earlier, an external organisation had done the formative research for the programme. Could you briefly tell me what were the key insights that came out of that?

The YPE4AH formative research key findings covered three main areas:

1) The behaviors and current understanding of family planning and SRH needs for 15 to 19-year-olds

- Adolescents had limited knowledge of family planning and GBV

- Barriers to FP access included fear of parents finding out, lack of funds, lack of confidence due to age

- Discussion between adolescents and Parents/Community Leaders is usually around puberty/menstruation, finishing school, and future careers. Preventing pregnancy, HIV/AIDS, SGBV, and drug abuse are not usually discussed.

- Social media is the main source of information on family planning for young people, followed by parents, health workers and friends; accessing information online provides needed privacy.

- Opinions of friends matter the most on sex matters

- Myths & misconceptions around family planning were also very common

- Lack of awareness of safe spaces for adolescents to discuss FP/SRHR and related issues in their communities

2) The political and economic landscape of Lagos and Kanos state as it pertains to adolescent health and well-being:

- Parents are not usually supportive of sexually active adolescents

- Health providers lacked concrete knowledge about the laws backing up ASRH services

- No knowledge of organisations hiring adolescents

- Adolescents prefer health providers of the same gender

3) The health system structure and processes for adolescent family planning and SRH programming

- Adolescents lack trust in healthcare providers

- Parents/Community Influencers do not view health providers as right sources of SRH information

- Youth Hubs will be well appreciated if designed properly

How was the synthesis of those insights done to use them appropriately in the design process?

Due to project timing, consortium partners started planning for the PDW prior to receiving the final findings of the formative research. When the formative research findings were shared, consortium partners ensured that the PDW plans and research findings aligned, and the PDW schedule included sections for each partner to lead. Consortium partners took part in weekly meetings to ensure that the workshop objectives were covered and that each partner was confident and prepared to lead their assigned sessions. Energisers and breaks between sessions were built into the schedule to ensure the workshop remained youth-friendly and high energy!

How were you able to ensure that the youth engaged meaningfully in the programme design workshop?

YPE4AH consortium partners all played a key role in encouraging youth engagement and active participation during the entire PDW. The PDW includes YAC members aged 15-19, consortium staff, as well as adult government and ministry stakeholders. A youth participation brief was distributed to adult participants prior to the workshop, in order to prepare them for sharing space and power with the YAC members. The brief outlined key principles of meaningful youth participation, and offered guidance for adult stakeholders who may not have been used to being side by side with young people in meetings and workshops.

Additionally, during the PDW, facilitators consistently reminded adult participants that they needed to use youth-friendly language and give the YAC members space to speak up and share their personal experiences. A celebrity ‘Youth Champion’ additionally took part in the PDW to facilitate youth panel discussions and help the young people feel more at ease, which really increased their comfort level during the workshop.

Consortium partners also made an effort to make YAC members and their guardians comfortable: parent/guardian permission was obtained for each YAC member to stay at the workshop venue for the duration of the PDW, starting the night before the activity began. Videos were prepared for the YAC members to introduce the workshop objectives in a youth-friendly manner. The videos also explained what the role of the youth would be, what was being asked of them, and what impact their participation may have on their lives and on the lives of other adolescents and/or young people. Consortium staff also emphasised that if the YAC members felt more comfortable using their own local language that was completely alright, and that translation would be available as needed. The workshop also included sessions at the end of each day where the youth shared their highs, lows and fun moments and anything else that they needed to be addressed.

During the workshop, YAC members took part in a ‘dream programming’ session to brainstorm ideas about what an ideal Hub or Spoke could look like, and what activities and/or SRH services will be offered. A ‘gallery walk’ approach was used in this session, where participants were divided into mixed groups that included both youth and adults, and different topics were written on flip charts. Each of these groups walked around the ‘gallery’ and wrote down their responses for each topic. The youth were responsible for being the writers for each flip chart, and the facilitators ensured that youth voices were heard and prioritised by allowing them to speak first. At the end of the PDW, the consortium had a ‘youth stamp of approval’ session where the youth were presented with the final Hub and Spoke designs. Even though they were co-creators, during the design workshop certain decisions were made by the government representatives and other consortium partners based on aspects like feasibility and viability to say what can and cannot be implemented. For example, young people indicated they wanted the Hubs to be ‘one-stop shops’ for all SRH services, but by necessity, some services would not be possible at the Hubs, such as removal of a contraceptive implant. There was also open discussion about whether parents should be allowed to go to the youth hubs. Initially, adult participants had suggested the parents should have access to the hub once a week but the youth said ‘No way! We don’t want our parents to come in every week’. They preferred the parents to have access on a quarterly basis, which was the final decision of the group. Hence, all those decisions had to be presented back to the youth for their final approval.

What are some of the tools that you have used in your work so far?

At GRS we use a tool called Dedoose. Dedoose is an easy-to-use, collaborative, web-based application that facilitates all types of research data management and analysis. Dedoose features are designed to help researchers quickly visualise, understand, and dig into the underlying nuances of qualitative research questions. Dedoose features help tie these data together, allowing you to generate charts based on descriptors and code weights/ratings, and, with a simple click on a bar or cell of a table, you can pull up all the stories that sit beneath the surface. You can quickly export the visualisations from anywhere inside of Dedoose along with all the underlying qualitative data and you are ready to drop the visuals into reports and presentations and report on the rich underlying qualitative findings.

At GRS, I used Dedoose to contribute qualitative data analysis to a research project on ‘Vuzu parties’ and their impact on ASRH in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. The research report detailed the feedback from young people on their experiences with the parties, in which alcohol, drugs, and unprotected sexual activity create risky environments for adolescents. GRS delivered the research report and recommendations to a partner organisation in Bulawayo.

What are you looking forward to the most at GRS?

I am excited to start this new project that aims to improve programme design and curriculum development for a holiday camp program. The holiday camp itself will improve access to SRH services for adolescent girls in Malawi through the GRS SKILLZ curriculum. The holiday camp is not very long, just about 3 to 4 days. I am really looking forward to that. The kick off meeting will happen in the next few weeks.

Thinking about your Fellowship experience to date, please describe for me a moment of success?

I am very proud to contribute to the construction of a ‘Youth-Powered Design Toolkit’ for GRS, preparing templates, guidance, and tools for the phases of the HCD process. I have organised existing tools, contributed new content, and prepared guidance for end users of the toolkit, GRS & partner organisation staff. The toolkit will aid in formalising the HCD process for GRS teams, and will be accompanied by HCD workshops that I will facilitate in the next month or so.

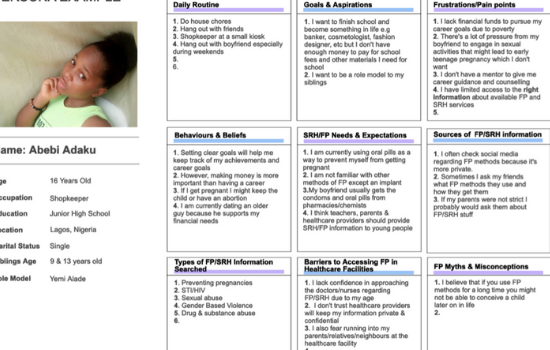

Another moment that made me feel proud was the persona development workshop in preparation for the YPE4AH curriculum development workshop (CDW). The session was facilitated by YPE4AH consortium staff in Lagos, with nine YAC members. The participants were asked to create three personas depicting a teenage boy, a teenage girl and a teen parent. The personas helped the YAC members in creating a unified understanding of the YPE4AH target audience needs, challenges and pain points. The personas are also currently being used as a point of reference for brainstorming the SKILLZ curriculum content and teaching methods.

Learn More:

- Twitter: @teetondigital

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/stowett/

- Organisational website: https://www.grassrootsoccer.org/

Copyright:

This story is copyright to Susan C. Towett and published on the HCDExchange website under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.